Labonte retirement plan "no big nothing" to him

Two-time Cup champion 'Iceman' stepping away after Texas

By David Newton, NASCAR.COM

November 3, 2006

04:01 PM EST (21:01 GMT)

FORT WORTH, Texas -- Somewhere down in Texas, seemingly in the middle of nowhere off a winding dirt road that goes on for at least 15 miles past tumbleweed, cactus and any other form of Texas scenery found in an old John Wayne movie, is a 1,500-acre ranch.

Outside the sound of a tractor engine or wind storm it is peaceful and quiet, much like the man who plans to settle there, nothing like the loud and smoke-filled environment he has been used to most of his life as stock car driver.

There is a bunkhouse that needs completing because the main house isn't large enough for visitors. There are fences to mend, brushes to clear and livestock to feed.

This piece of land a hundred miles south of San Antonio is where Terry Labonte, the 1984 and '96 Winston Cup champion, plans to spend much of his retirement.

This is where the 49-year-old native of Corpus Christi, Texas, will hunt and fish and, as his brother and 2000 Cup champion Bobby Labonte says, "work like a dog.''

"He once made the comment that he could live there for 10 years and never run out of things to do,'' said Labonte's wife, Kim.

Now he'll have time to do them.

But before ''Texas Terry'' settles into this new lifestyle he has one more race to run. Fittingly, it'll be in the state where he grew up and began his career.

Labonte began preparing for Sunday's swan song at Texas Motor Speedway two years ago when he announced his "Shifting Gears'' farewell tour that called for him to run a limited schedule for Hendrick Motorsports in 2005 and 2006.

He went somewhat above his 10-race per season limit after agreeing to help two other famous Texans, former Dallas Cowboys quarterbacks Roger Staubach and Troy Aikman, jumpstart Hall of Fame Racing.

But there are no regrets.

There is no looking back.

"I still love the sport,'' Labonte said. "I've been very fortunate to be a part of it for so long. I want to do something else, and I don't feel bad about it at all.''

The only thing the driver known as the "Iceman'' feels bad about is the hoopla surrounding his final race.

It began with a Thursday night dinner in which more than 400 family, friends and fellow drivers honored the man that collected 22 victories in 847 starts, who once owned the streak for most consecutive starts at 655.

It will continue through Sunday when Labonte climbs into the No. 44 Chevrolet with a special paint scheme commemorating each of his 12 victories for HMS, including a portrait of his Victory Lane celebration at Texas in 1999 on the hood.

He will come out last during driver introductions and then lead the parade lap no matter where he qualifies.

There will be a video tribute entitled Somewhere Down in Texas shown on the large infield screens.

It's far more fuss than a man known for his modesty and shying away from the commercialism of the sport, a man who celebrated wins with a smile and shake of the hand instead of burnouts and doughnuts, would want.

In a world of multi-colored paint schemes Labonte is as vanilla as they come.

"As long as they don't make me shoot out of a cannon pre-race I'll be fine,'' Labonte said.

No cannons, but there are so many tributes that not even the family knows everything.

"He keeps asking us why everybody is doing this stuff for him,'' said Labonte's 23-year-old daughter, Kristy. "He keeps saying, 'I'm not that big of a deal.' ''

But Labonte is big in NASCAR as was evident by Thursday night's gala in which one of his old driver's uniforms was auctioned off for $16,500.

And in a state where big is the norm, he is a very big deal.

"It's going to be a special moment when he gets introduced on Sunday,'' said Rick Hendrick, Labonte's car owner since 1994. "He's one of the nicest people I've ever met and probably one of the most unselfish professional athletes I've ever met.

"He doesn't promote himself. He doesn't want it. He doesn't need it. We're all here to make sure he gets it.''

Dose of reality

Labonte was enjoying one of his first race weekends away from the track two years ago, doing what many avid outdoorsmen do on a lazy Sunday afternoon.

He was shopping at Bass Pro Shops in Concord, N.C.

As Labonte walked through the seemingly endless rows of rods and lures he looked at his watch.

"I was like, 'Oh, wow! The race is about to start! What are all of these people doing? Don't they know the race is about to start?' '' Labonte said. "It's like there is a whole other world out there. You're involved in this so much that you think it's all there is, and it really isn't.''

Labonte has known no other world outside the white lines since climbing behind the wheel of the quarter-midget car his father bought him at age 7.

From the days when he had to lie to track officials about his age so he could race stock cars as a teenager until now, racing has been a way of life.

"I think I'm going to be 50 years old [on Nov. 16], but I was 16 for three years,'' Labonte said with a laugh.

The only time this lifestyle seemed in jeopardy was in 1977, when because of a shortage of money Labonte didn't show up at Houston's Meyer Speedway.

Fortunately, the track promoter noticed the young driver that led the rookie points standings wasn't there and called him at home. He told him to come meet Billy Hagan, a businessman and car owner from Louisiana.

Hagan not only kept Labonte in racing, he got him to move to North Carolina to get involved in NASCAR. In 1978, in his first Cup start at Darlington Raceway, Labonte finished fourth.

"I've never seen so many wrecked cars in my life,'' laughed Labonte, who still has a home in Thomasville, N.C. "It was the longest race I'd ever run in my life. It took all day.''

Two years later, at the same track in the South Carolina sandhills, Labonte beat David Pearson and Benny Parsons for his first win.

It was such a thrilling finish that Labonte's wife and much of the crowd initially thought Pearson won.

"We all went down to Turn 1 and David Pearson and Benny Parsons and somebody else hit the wall, and there was oil on the track,'' Labonte recalled. "I didn't hit the wall and so I beat Pearson back to the line before the white flag.

"I passed him coming off 4 to the caution and we raced back to the caution. ... I don't even think he saw me coming.''

Quiet man?

The Victory Lane celebration that hot, muggy day in Darlington wasn't much different than the celebration there in 2003 when Labonte won his last race.

"He just doesn't want the limelight,'' Hendrick said. "It's almost like he's embarrassed in Victory Lane. We're jumping all around excited when he wins a race. He just gets out of the car with a smile, holds up the hand and takes a picture and goes to changes his clothes.''

That doesn't mean Labonte doesn't like to celebrate. He proved that after wrapping up his first title at Riverside, Calif.

"It was pretty wild,'' said Dale Inman, Labonte's crew chief at the time. "Terry said his hair hurt when he got up the next morning and had to comb it.''

Gary DeHart, who was the crew chief when Labonte won the title in 1996 at HMS, understands.

"You just have to know Terry and how he is,'' said DeHart, the safety director at HMS. "Yes, he showed emotion when he won it in '96. Did he show as much emotion as some people do when they make great accomplishments like that? Probably not.

"That's why they call him the Iceman.''

Ken Schrader, who helped lure Labonte to HMS in '94, knows Labonte's no-so-quiet side better than most as was most evident during the gala-turned-roast.

"He puts on a good front and all, but he's not that damn quiet,'' Schrader said.

Labonte smiled, recalling the time he put police tape around Schrader's motorcoach.

"That's because it was a crime scene the night before,'' Schrader quipped.

The two play off of each other like Jerry Lewis and Dean Martin. Four-time champion Jeff Gordon, Labonte's teammate at HMS, was shocked when he saw this side of Labonte at the gala.

"I've learned more about Terry tonight than in the past 12 years,'' he said. "I've never heard you talk so much.''

He learned more than he bargained for when Labonte recalled the Thursday night before the 1996 NASCAR banquet in New York City, where Schrader crowned him the champion with an ice bucket at 3 a.m.

Schrader reminded how they did their best to run up the room tab at the Waldorf Astoria to $25,000 with undisclosed beverages.

"I was right at it and got home and here comes the kids wearing those Waldorf Astoria robes,'' Labonte said. "It was a fun weekend. It was worth every penny of it.''

Texas temper

Cool. Calm. Controlled.

That's the way most describe Labonte on the track. But do something to get him mad and watch out.

"Terry is real mild mannered, but when he gets mad he will go after you,'' Hendrick said. "I remember at Bristol one time Lake Speed was messing with him. He finally got into Terry and wrecked him.''

But Labonte, as he did more than once, never got out of the car or raised his voice. He simply demanded his crew fix the car, which under normal circumstances would have been parked, good enough for him to go back out for payback.

"He was called to the NASCAR trailer after the race,'' Hendrick said. "They said, 'Terry, you wrecked that guy on purpose.' Terry looked at them and said, 'Yeah, he wrecked me.' He didn't deny it or say he slipped. He just said, 'Yeah, I did.' ''

But for the most part Labonte is known for keeping his cool, even when he doesn't deserve it.

Such was the case after the late Dale Earnhardt spun him out for the win on the last lap of the March 1999 race at Bristol.

As Earnhardt took the checkered flag, Labonte sat on the backstretch plotting his revenge. He was going to wait for Earnhardt to come back around on his victory lap, throw the car into reverse and T-bone the famous No. 3.

"I'm sitting there thinking he may be going to Victory Lane, but he'll be going with the No. 5 stuck in his side,'' Labonte said.

Labonte had everything timed perfectly until he put the car in reverse.

"The transmission broke,'' he said. "Later on, everybody told me how well I handled that.''

Gordon always heard of Labonte's temper but never saw it. He can't remember having had an issue with his HMS teammate, even when he lost the 1996 title to Labonte by 37 points.

"There were times when it was tight that there was a little tension between the teams back at the shop,'' he said. "Probably more bragging rights than anything else.

"But as far as me and Terry were concerned, there was no animosity, no tension at all.''

Hendrick knows what would have happened had there been, recalling a time when Labonte punched Michael Waltrip between the eyes "like a lot of us have wanted to.''

"He's mild mannered,'' Hendrick said, "but when he's had enough, man, you get out of his way.''

Friendly rival

Dale Earnhardt Jr. remembers vividly the first time he heard his dad invite Labonte to go hunting.

"I am like, 'Wow, he likes Terry. Terry must be really cool,' '' said the son of the seven-time Cup champion.

Despite what happened on the track, Earnhardt and Labonte put their differences aside for their common love of the outdoors. Well, at least after a few months.

"It kind of screwed up our hunting trip that year,'' Labonte said.

Hunting was one reason Labonte purchased the ranch in Texas, although those close to him laugh because he would rather bring the deer home -- as he used to do with stray dogs -- than kill them.

Bob Labonte jokingly says his son has names for half of the wildlife.

But if you want to engage Labonte in a conversation that exceeds a couple of words, just talk hunting or fishing.

"One of the longer conversations that he and I had [was after] I did some fishing on Rick's boat,'' Gordon said. "I remember talking to him about that and seeing him perk up and having that interest.''

Some of Hendrick's best times on his boat have been with Labonte and Schrader. He starts laughing at the thought of one of their stories, and loses his train of thought when recalling Labonte's laugh that is somewhat unusual but infectious.

He wishes Labonte had an interest in television commentary, and so did others after hearing him on Thursday.

"When he gets up in front of people and speaks to a crowd he reminds me a lot of Hulk Hogan,'' said Hendrick, who met Hogan through a sponsor. "Hulk Hogan would be behind the stage bashful and shy.

"But man, when he walked onto the stage he was wide open.''

Earnhardt Jr. has only seen the quiet side. He knew Labonte for years before the two spoke, and he remembers that conversation as well as he does the hunting invitation from his father.

It happened at Watkins Glen when he was in Schrader's motorcoach with Labonte, Dale Jarrett, Rusty Wallace and a few other drivers.

"He nudges me and says, 'Hey, I see you are still not wearing the Hans device,' '' Earnhardt Jr. said of the head and neck restraint drivers now are required to wear. "This was before the rule and he said, 'You ought to wear one. I would like to see you stick around for a while.'

"Those were the first words the man ever said to me in my life. So the next week I immediately starting wearing the Hutchins Device, but he pushed it and if Terry Labonte asks you to do it, you do it.''

Brotherly love

As Labonte packed his belongings in boxes and prepared for the move to North Carolina his little brother began moving into his room.

"I was, 'Dude, I get the room with the phone,' '' Bobby said.

That was the only time Bobby remembers ticking off Terry, on or off the track.

"Everybody was crying,'' Bobby remembered. "It wasn't no big deal to me. I was glad he was leaving.''

Bobby can't say the same about Terry leaving the sport. There are few he can or wants to walk to like he does his brother. He'll miss that more than the competition.

"I've got mixed emotions right now,'' Bobby said. "I'm gonna be upset because I hate that he's not going to be around to talk to. But then, I get his fans. So that will be good.''

Bobby is slightly more outspoken than Terry, and is much more upfront with his wry sense of humor.

"Bobby will let you know his moods,'' Inman said. "The only thing that will give Terry away on his mood is the expression on his face.''

As different as their faces are, fans often get the two confused. It happened a few weeks ago at Lowe's Motor Speedway when a fan told Bobby how much he as going to miss seeing him next season.

Bobby played along, as he often does, never giving away his identity.

"Maybe with him being gone they'll figure out that was me,'' he said with a smile.

Sometimes the confusion happens with people who should know better. That happened in 1996 when Bobby, then the driver of the No. 18 Interstate Batteries Chevrolet for Joe Gibbs Racing, was mistaken for Terry by a reporter in the back of a Hendrick hauler at Indianapolis.

Bobby, with his hand over the name on his uniform and Terry a few feet away, spent 10 minutes answering questions about HMS.

"Those guys were rolling in the floor laughing,'' Bobby said of the Hendrick crew. "[When the reporter finished] he was, 'OK, thanks, bye.' I was, 'OK.' ''

Special moment

In Bobby's office is a picture of him and then-owner Joe Gibbs in Victory Lane with Terry and Hendrick.

It's one of his most prized possessions.

The picture was taken after the 1996 finale at Atlanta Motor Speedway, where Bobby won the race and Terry wrapped up his second title to give him a record for biggest gaps between championships.

"It was one of those storybook endings,'' said Bobby, who suggested the night before that would be the way to cap the season.

The brothers, the only two in NASCAR history to win Cup titles, proudly circled the track together after the race. They then headed to Victory Lane, where Terry's voice actually cracked during the trophy presentations.

"That's the first time I've gotten emotional,'' Terry said at the time. "I was a little surprised at myself.''

The emotions of that day weren't topped until 2004 when Labonte's son, Justin, collected his first Busch Series victory at Chicago.

"That was definitely the most emotion I've seen out of Terry at any time,'' Kim said.

Kristy agreed.

"When you look at the pictures now, he was just smiling so big,'' she said. "He still talks about that all the time. That's one of the biggest victories of his career. I think it meant more to him than Justin.''

Bobby would like nothing more than to see his brother go out with one more win, but he knows that isn't realistic.

So does Terry. One of the hardest things about running a part-time schedule is he gets a part-time crew. Outside of a third on the road course in Sonoma, Calif., he's finished no better than 17th.

And no, Bobby wouldn't let his brother win if it came down to the two on Sunday.

"I don't give him a birthday present,'' he said. "I don't know why I'd give him a going away present.''

No big plans

Labonte doesn't know what it will be like when he rounds Turn 4 on the final lap on Sunday.

"I hope I have a half lap lead,'' he said.

Labonte also isn't sure what he will do after racing beyond hanging out on his ranch, keeping tabs on his auto dealership and helping Justin with his racing career.

"I don't have no big plans,'' he said with a shrug. "No big nothing.''

That doesn't surprise his wife.

"We haven't actually sat down and talked about five years and 10 years from now,'' she said. "But if it was up to him he'd be a rancher. He loves to be out there and there's always stuff to be done.''

One thing is certain. Labonte is ready to walk away. There are no comebacks or second farewell tours in his future.

When a car owner asked him at Charlotte if he would like to race two weeks later at Atlanta he didn't hesitate.

"Nope,'' Labonte said. "The guy says, 'So I don't need to talk money?' I said, 'Nope.' I just don't really have no desire to. Maybe after I sit out for a while I might change my mind or start missing it or something, but as of right now, I sure am looking forward to life after the Texas race.''

From now on Labonte's racing will include a TV remote instead of a steering wheel, a recliner instead of a fitted seat.

"Somebody asked me if I'll watch the races,'' Labonte said. "I said, 'Yeah, during commercials on the football games.' ''

Not exactly what NASCAR chairman Brian France would want to hear, but Labonte isn't concerned about who he offends as he was early in his career.

"Well, there's politics in everything,'' Labonte said. "There were a lot of things you couldn't say back then if you wanted to be in the sport. People don't realize that, but that's how it was.''

Labonte isn't planning a book like the one recently released by Bill Elliott in which the 1988 Cup champion criticized NASCAR for not having a traveling safety crew. He doesn't even agree with Elliott on that matter.

But there are things Labonte doesn't like about the sport. He says the 36-race schedule is too long and he's not a fan of the Car of Tomorrow that will be introduced in 2007.

"I know why they did it,'' he said of the COT. "I know there's a lot of good features. I think they could have incorporated a lot of those safety features in the current car. Once they got too far down that path, it was too far to turn back.''

Labonte also says the races are too long, something he didn't realize as a driver.

"I don't know how in the world you can watch them on TV,'' he said. "I've never watched a whole race start to finish.''

Labonte is glad he weaned himself off of driving instead of quitting cold turkey. It's helped him appreciate what he had and what he won't miss.

"Probably the best thing about it was waking up on a Sunday morning and not being in Loudon, New Hampshire,'' he said. "That was pretty exciting.''

Labonte's lips curled up around his gray mustache. He was half serious and half poking fun.

But he's completely serious about enjoying life after racing.

"There comes a time, I don't care what sport you're in, that you've got to walk away,'' he said. "I've been very fortunate over the years. I've won a couple of championships, done a lot of things, met a lot of cool people and gone a lot of cool places.

"It's been a dream of a lifetime.''

--------------------------------------

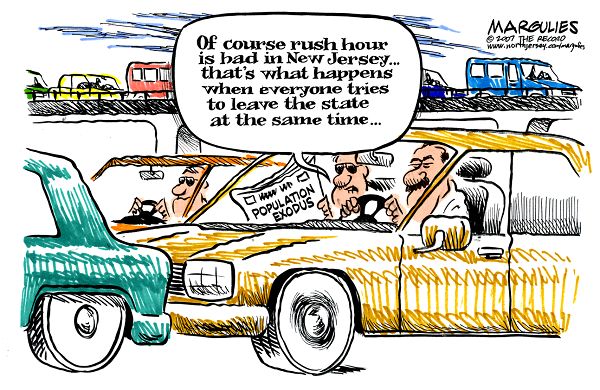

Bill's Comment: If the world only had more classy athletes like Terry Labonte, then a lot of today's athletes (e.g., "T.O.", Randy Moss, Allen Iverson) would not get such a bad rap. Unfortunately, negativity rules the media these days.

Friday, November 03, 2006

Labonte retirement plan "no big nothing" to him

Posted by William N. Phillips, Jr. at 11/03/2006 06:23:00 PM

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment